The summer of 1985 was pretty hectic here in NYC. Crack had taken hold of the city by then. Not the imaginary crack of DipSet or G-Unit, but the real crack up in Breevort, up in Taft, up in Baisley, and the 40 Houses. The real crack that forced grandmothers to have to raise their grandbabies. That is, if they weren’t selling crack too. Everyone and their grandma would be selling it because it was in demand that much.

Black neighborhoods were already established as the outposts where you went to get all the vices you craved, because that is how the system works. Just like you might go to a mall or an outlet complex to do your shopping, the drug trade works the same way. These drug outposts are set up and the local people are used to work the outlets. These local people are the last stop in the chain of drug distribution. They aren’t part of the production division which refines these narcotics from farmed plants through a chemicalization process. These local people aren’t part of the transportation division which has to move tremendous amounts of these narcotics over many miles, requiring boats and planes and devices that can accomodate large loads. The local people surely don’t own the factories and manufacturing centers that produce the vials and containers that these narcotics are sold in. These local people aren’t even part of the process that decides which drugs go to which neighborhoods so that the communities may be studied for the long term effects of these drugs. Nope, when it comes to dope the Black communities are just the retail division. The last stop before the consumer.

In 1985, law enforcement made little distinction between the retailer and the consumer when it came to the prosecution of drug possession. The media trumpeted the center city violence that was a by-product of all the money that was up for grabs. This in turn forced the police to come down hard on the local dealers in their efforts to hold press conferences showing Black people criminals were being handcuffed. This is where T.C. and I come in the picture…

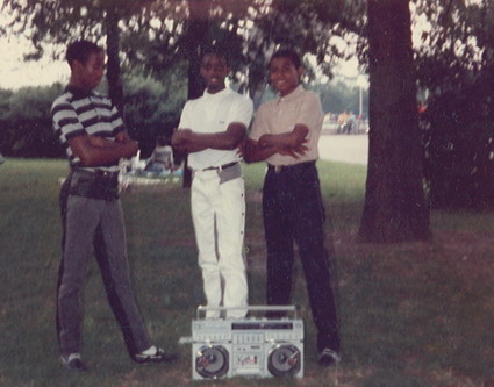

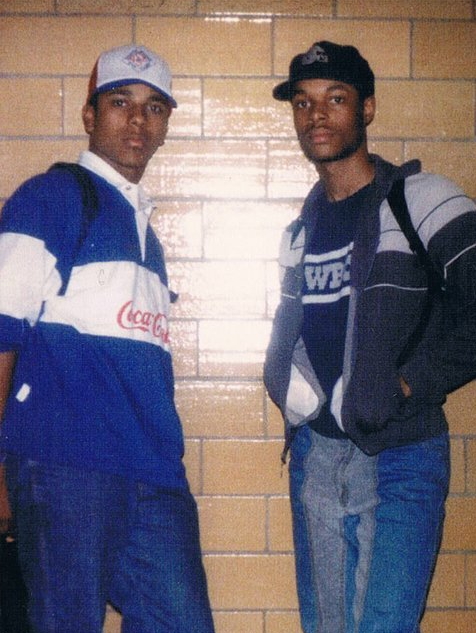

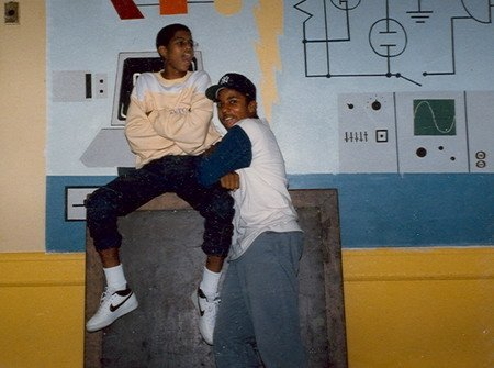

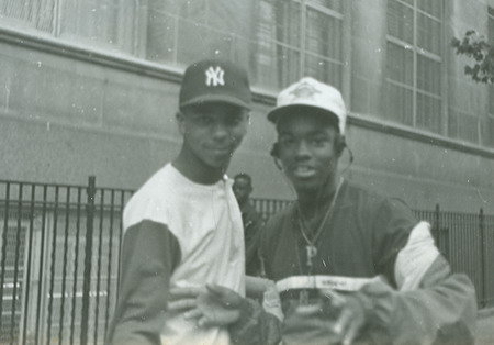

T.C. and I were not from the side of the neighborhood that the drug trade was conducted on. Trees lined the streets of our block and most of the houses had detached garages and manicured lawns. LOUIS ARMSTRONG’s house was around the corner as well as radio personality FRANKIE CROCKER and former baseball player TOMMIE AGEE. But even with that relative prestige there was still a call to us from the other side of the neighborhood where the working class people lived. Its almost as if they lived a realer ‘Black’ experience than we did. Nevermind the fact that our parents had struggled to graduate college and squirrel away their pennies to buy their homes. For T.C. and I as well as many middle class Black kids it wasn’t enough for us to have the melanin to confirm our ‘Blackness’. We needed something more.

T.C. and I were friends with a 5% dude named BAR-KIM (R.I.P.) whose government name was BARRY. He was from the other side of the ‘hood. Back in our graffiti days BARRY used the tag name BAR ONE. He always wanted to get up in our black books because he would see the names of writers from places he had never been to. By tagging up in someone’s black book you got to travel to other places. It was a chance to become immortal. T.C. and I now wanted what BARRY had which was the right to stand on the corner. The right to claim a 5ft. square flag of concrete pavement as your own place. When people would pass by BARRY they would acknowledge him and defer to him as though he was the overlord of that corner. BARRY was willing to share his corner with us, but we were going to have to help him with the administrative duties. STAT and LIL’ MIKE were in charge of the opposite corner, but they weren’t as committed as BARRY was. I didn’t think BARRY ever slept because I would see him on that block at every conceivable moment. BARRY had our ticket to street credibility within the neighborhood and he could see that we wanted it badly. One summer weekend BARRY made us an offer. If we would hold down the corner with him, direct traffic and look out for police he would give us a piece of his profit. If we were out there for about 10 hours we could have $50 dollars. In 1985 $50 dollars was a lot of money. Shit, I could use $50 dollars now and its more than twenty years later. The really good money though was in flipping packs. The actual selling of 100 vials of crack. So this was what we wanted to do. To take the express elevator to the top of the game.

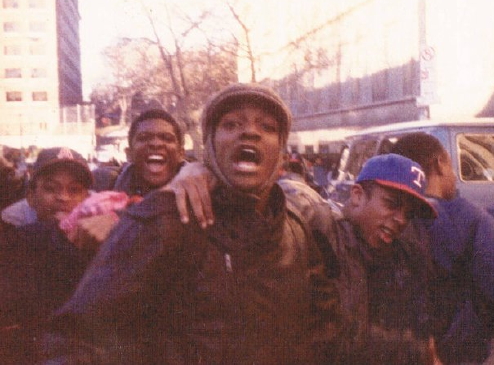

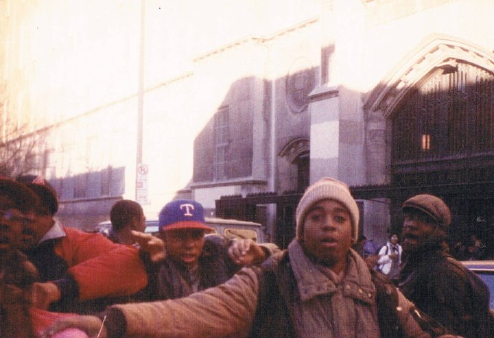

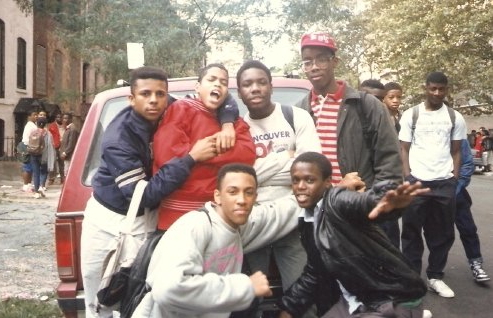

Holding down a corner is without a doubt the hardest, most nerve-wracking job that you can ever do. There isn’t a minute to relax. People are steered to you on foot, on bicycle, in cars. You explain to them what you are holding and what the prices are. They have to move quickly and if they take too long to decide you don’t serve them. This teaches them to be decisive and to understand the pace of the block. The big danger were the undercover cops. Their cars were indistinguishable from all the vehicles that passed through the block. The busiest day of the week for them was Tuesday. To this day, I know people who call it ‘Task Force Tuesday’ and they don’t even sell or buy drugs. But even they know.

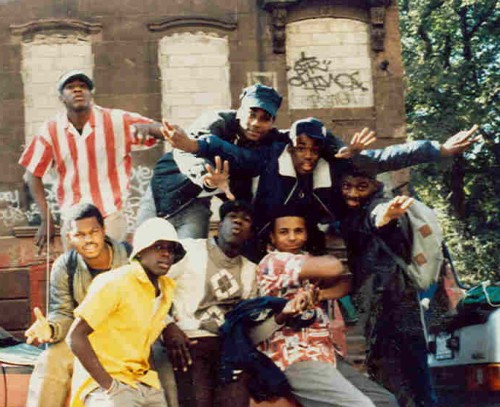

The lesson that T.C. and I were taught from this experience was how difficult selling drugs is around the people that you grew up with. Crack cocaine was such a powerful drug. The dependency it caused was relentless. The users were rabid and ravenous. I had never registered any of the buyer’s faces before, and I had never been on the block during a pay day either. Everybody was working their piece of concrete. The harried scene was surreal. It was as if crackheads were materializing out of thin air. Then they would disappear from you in the same manner as if the night shadows swallowed up their bodies. BARRY was moving wild amounts of work. He needed T.C. and I to help maintain order among the desperate drug abusers.

Some were returning for the second, third, tenth time that evening. I looked at them as if they were inhuman. It was as if their souls were removed from their bodies. The users were so paranoid that it offended me to witness them. Their constant state of panic annoyed me because I thought that it might be contagious like smallpox. The jittery twitching and repeated scratching wasn’t the only telltale idiosyncracy. These people spoke inaudibly because they were saying 100 words per second. I hated them. I hated their look. I hated their smell.

As the night moved on I found out how spiritually draining it would be to stand on the corner as a profession. We were approached by a tall hooded man with the most godawful filthy jeans on and a ridiculous pair of no name sneakers. There is nothing worse than a bummy crackhead and I was ready to kick this man in the azz just for being a junkie. My attitude changed when I saw the man’s face. He was my little league coach, LESTER TAYLOR. BIG LES was like the coolest motherfucker ever. He was a neighborhood fixture because he had been a college worthy cager back in the day. I remember that BIG LES always had a crispy pair of sneakers on when he came out to the field. I made my mother buy me a pair of Puma cleats because BIG LES always wore suede ‘CLYDE’ Pumas. He was tall and strong and loud and proud. More importantly, he was a really good coach. He never yelled at me when I made errors. He didn’t make fun of me for being a fat kid either. BIG LES didn’t force me to play catcher because in little league baseball the fat kid always has to play the catcher position. How in the world does this guy go from being a teacher, a hero, to being the biggest loser on the planet?

When T.C. saw LES he was as sad as I was. LES head dropped below his shoulders. He realized that we recognized him and his shame became an almost unbearable weight. I watched LES go to BARRY and give him a crumpled ball of cash. BARRY cursed at him for giving him the money in that manner. LES hunched over even further. BARRY told him that he wasn’t going to give him another sale unless he brought money that hadn’t already been used to wipe someone’s ass. LES skulked away into the darkness without raising his head to look back at T.C. or me.

Seeing LES that night was actually like going to my very first funeral. That little kid that played third base in little league was killed that night. I had to grow up now and remove the cover of innocence that had shielded me up to this point. Seeing LES made me angry at him for being a drug abuser. I became angry with myself for ever giving him the respect of an older brother. I was angry with BARRY, STAT and MIKE and all the other kids that sold crack. My anger became self-destructive and I turned it onto other people. I needed an outlet to vent. New York City was a big place. It almost wasn’t big enough to contain me.